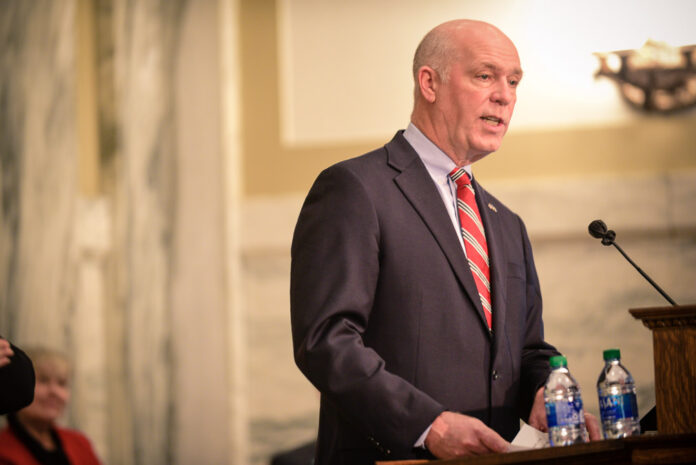

HELENA — Gov. Greg Gianforte said recently that he wants at least 10,000 jobs paying more than $50,000 a year added to the state economy this year, putting a firm metric to the Republican governor’s widely publicized pledge to lead a Montana “comeback.”

“How many jobs exist in the state of Montana over $50,000 a year? And we benchmarked Q4 of 2020, and our goal this year is to add 10,000 jobs in Montana over $50,000,” he told Montana Public Radio reporter Shaylee Ragar in an interview published June 22. “And I think that’s an achievable goal.”

But how precisely will the state measure its progress toward that goal? How many jobs in the state already pay that much? And how many well-paid jobs was the state adding under Gianforte’s Democratic predecessors? Answers to all three questions help put the governor’s goal in context.

Data provided to Montana Free Press by the state Department of Labor & Industry indicates Montana had about 132,000 jobs with wages above the $50,000 threshold in the fourth quarter of 2020. That’s a 9,800-job increase over the same quarter of 2019, even given the economic disruption stemming from the COVID-19 pandemic.

In the last quarter of 2020, shortly before Gianforte took office, about one in four Montana jobs paid above the $50,000 threshold. That’s up substantially from the quarter before former Gov. Steve Bullock took office eight years earlier, when the fraction of Montana jobs above the threshold was closer to one in six.

Since the beginning of 2011, the first year the labor department provided data, the number of $50k-plus jobs in Montana has grown at an average rate of 6.7% a year. If that trend holds, the state will add about 8,900 $50,000-plus jobs in 2021, slightly less than Gianforte’s goal.

As he ran for governor last year, Gianforte, who entered politics after successful stints as a tech entrepreneur, built much of his campaign around a promise to lead Montana’s “comeback” — both from the economic turmoil of the COVID-19 pandemic and what he called years of mismanagement under Democratic leadership in the governor’s office. His campaign published a 16-page “Montana Comeback Plan” that he routinely cites as a policy blueprint.

Since taking office in January, the governor has signed into law a raft of measures that cut taxes on entrepreneurs and higher-income earners, saying lower taxes on the wealthy will boost Montana’s economy by encouraging business growth and migration from other states. Gianforte also made Montana the first state in the nation to stop offering expanded pandemic unemployment benefits this month, saying they were discouraging Montanans from returning to work as the state’s tight labor market becomes an increasing challenge for employers.

As Gianforte looks to steer the Montana economy toward his 10k-above-50k goal, that tight labor market could be a complicating factor.

Missoula-based economist Bryce Ward of ABMJ Consulting said in an interview that even if well-paid job openings are available, people to fill them have to come from somewhere, potentially pulling workers from lower-wage jobs. He noted that labor force participation, the fraction of the working-age population that is either employed or looking for work, is down somewhat from pre-pandemic levels, however.

“We do have slack. There are people who used to be working who are not. If you bring those people back en masse, then yeah, you can probably fill these new higher-wage jobs without squeezing out lower-wage jobs,” Ward said. “But it’s entirely possible that the only way to fill these high-wage jobs is to leave certain low-wage jobs vacant.”

Montana State University economist Carly Urban said the state has two primary routes to increasing the number of higher-wage jobs: attracting remote workers (a stated priority for the governor) or expanding industry sectors with the capacity to offer higher wages. She’s somewhat skeptical that the latter will be an easy route for Montana.

“The sectors where Montana is really dominant, like tourism, are probably not going to be the ones generating those jobs,” Urban said.

“The sectors where Montana is really dominant, like tourism, are probably not going to be the ones generating those jobs.”

Montana State University economist Carly Urban

Gianforte has also discussed ways to bolster Montana’s manufacturing sector, which typically pays workers relatively well. One of the tax policies he signed into law this year, for example, was designed to rework the state’s corporate income tax system to shift some tax burden from Montana-based manufacturing companies to Amazon-style retailers that sell into the state.

Urban also said it’s important to keep an eye on not just the number of workers earning good salaries, but also how people with lower incomes are faring in the state economy. It’s clear, she said, that some people have been doing quite well despite the pandemic while others have struggled. She noted that childcare has become a major challenge for many Montana families, in some cases keeping parents from being able to work.

Additionally, Urban pointed out that the statewide target doesn’t necessarily mean the governor will hold himself accountable for bringing jobs to smaller towns in addition to already booming urban centers like Bozeman and Missoula.

“My concern is that, in Montana, if those jobs are starting to exist, they will likely start existing in the bigger cities,” she said.

Both Ward and Urban also noted that if Gianforte succeeds in meeting his job-creation goal, it will be difficult to determine whether to credit his conservative state-level economic policy or other forces, such as the billions of dollars in federal stimulus money flowing into Montana.

Gianforte has criticized the latest round of stimulus spending, the American Rescue Plan Act, which is funded by deficit spending and was passed by congressional Democrats and President Joe Biden over Republican opposition. Even so, he’s routinely touted spending ARPA dollars that are being allocated through state government. For example, the governor’s office said June 29 that the state is allocating $38 million of stimulus money to efforts to expand access to affordable childcare.

“The governor believes the federal government spending trillions upon trillions of taxpayer dollars is fiscally irresponsible and, ultimately, a burden our kids and grandkids will bear,” Gianforte Press Secretary Brooke Stroyke said in a statement. “That’s why the governor is looking to invest these dollars in long-term investments that will benefit our kids and grandkids through expanding access to reliable broadband, improving water and sewer, and stabilizing our child care system.”

The state labor department said it’s estimating the number of jobs at the $50,000 pay threshold using information submitted on a quarterly basis by employers who participate in the state unemployment insurance program. That means the figures include most Montana workers paid on a wage or salary basis, but exclude people who are self-employed or earn their income from business investments.

DLI Public Information Officer Jessica Nelson said the agency determines whether each job in the unemployment insurance data meets the $50,000 threshold by looking at how much the job has paid over four previous quarterly filings. That means workers who have received raises bumping them over the $50,000 threshold are counted as a job created in the high-wage category once their total pay for the past year reaches that level. It also means that workers who are newly hired in high-wage jobs aren’t counted until they’ve earned $50,000 in their new position.

Montana’s overall wage employment generally fluctuates with the seasons, with the labor department’s data indicating that roughly 50,000 more jobs are routinely on the books during summer months. Nelson said that variation is less pronounced in the higher-wage jobs, in part because few seasonal jobs pay well enough to get their workers over the $50,000 threshold in only part of the year, and in part because the “lookback” method tends to smooth out seasonal variation.

Ward also said it’s important to keep inflation in mind when evaluating the $50,000 threshold, given that prices have been rising for the things people spend their salaries on, such as houses. The Wall Street Journal has reported, for example, that as of May consumer prices were up 5% relative to last year.

“It’s easy to say, ‘Oh we’ve got these new jobs,’” Ward said. “But the real question is: Are we better off?”

This story is published by Montana Free Press as part of the Long Streets Project, which explores Montana’s economy with in-depth reporting. This work is supported in part by a grant from the Greater Montana Foundation, which encourages communication on issues, trends, and values of importance to Montanans. Discuss MTFP’s Long Streets work with Lead Reporter Eric Dietrich at edietrich@montanafreepress.org.

Credit: Source link