Analysis

9 February 2022

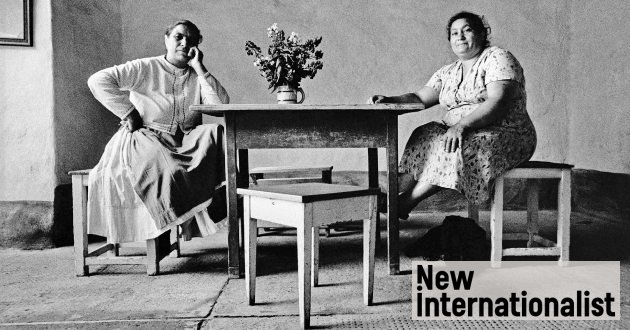

MAGNUM/JOSEF KOUDELKA

There are upwards of four million Romani people across the world, though estimates vary considerably. The lack of precise figures is partially because many governments are reluctant to recognize Romani ethnicity as a census category and because many Roma are hesitant to self-identify for fear of unfavourable consequences.

Most Roma are settled in south eastern Europe, the area of the historical Byzantine Empire into which they migrated from Western Asia around the 10th century, and in central Europe, the area of the historical Habsburg Monarchy. As the Byzantine regime began to collapse in the 15th century, many moved on into the Habsburg domain. There are also sizeable Romani populations in other regions of Europe, as well as in the Americas and Australia.

Perhaps the most obvious marker of Romani ethnicity is the Romani language (also known as Romanes). It is spoken in a variety of dialects that are usually mutually intelligible. However, there is no ‘standard’ Romani language and the tendency to insert words, idioms and phrases from dominant local languages sometimes limits the ability of Roma people from different countries to communicate effectively on more formal topics.

Language provides the most important clues about the preEuropean origin of the Roma

Romani people also share many customs and beliefs. For example, Roma tend to observe a separation between upper and lower body, and to maintain certain boundaries between age groups and genders. Women’s clothes are washed and hung out to dry separately from men’s, and upper and lower body garments are separated.

During periods of mourning, restrictions are placed on washing, shaving, and preparing food. Roma also reserve certain days of the year for pilgrimages to holy sites. Those days are used for large-scale gatherings, often incorporating social contacts, marriage arrangements, business transactions and conflict resolution. Many Roma communities settle conflicts through panels of ‘judges’ or ‘elders’.

These traditions constantly evolve, however, and their observation varies between families and communities and particularly among groups that are often referred to as Romani ‘nations’. The latter are usually communities of related kinship units that share a Romani dialect, typical dress codes and often trace their origins to a particular region. They often share a preference for a certain portfolio of occupations and carry names that reflect these traditional trades (such as Coppersmiths or Horse Traders) or historical regions (such as Lithuanian Roma or Mountain Roma, the latter referring to the Carpathian highlands of southern Poland).

Some populations have abandoned the Romani language in recent generations but retain a set of Romani-derived words that are used in everyday conversation. This is found particularly in Britain, Scandinavia and the Iberian peninsula. Some populations are known to have spoken Romani in the past but have completely assimilated linguistically: they include many Hungarian Roma as well as the Beyash of Central Europe, whose language is a dialect of Romanian, and the Ashkali in the Balkans, who speak Albanian.

MAGNUM/JOSEF KOUDELKA

Indian origins

Language provides the most important clues about the pre-European origin of the Roma. Philological research in the late 18th century established that the Romani language was of Indic origin and was related to the language then labelled Hindustani, and now known as Hindi or Urdu. Subsequent historical-linguistic research has shown that Romani shares its structural core with Hindi and Urdu, along with other languages of the central Indian subcontinent while also sharing some traits with the languages of the northwestern regions (such as Kashmiri). That seems to point to an early migration within the Indian subcontinent.

Overall, the linguistic evidence suggests that a breakaway from the languages of the Indian subcontinent – indicating migration out of India – happened toward the end of the first millennium CE. Linguists have taken slight Iranian and Caucasian influences on Romani vocabulary as evidence of a gradual migration westwards with interim settlement and contacts in the relevant regions along the way. The strong imprint of Medieval Greek on both the vocabulary and grammatical structure of Romani testifies to a subsequent prolonged co-existence with Greek-speaking populations in the Byzantine Empire (Anatolia and southeastern Europe), possibly as early as the 12th or 13th century, and lasting up to the 15th century.

With no historical documentation, there is still speculation as to what drove the Roma west. The self-appellation ‘Rom’ is derived from the caste name ḍom, which is still used today in India to label populations that specialize in mobile service trades: metalworkers, manufacturers of tools, horse-traders, healers and entertainers (musicians, dancers, palm-readers and so on). Other populations outside of India have also maintained caste names, speak Indian languages and specialize in itinerant trades. They include the Dom of the Middle East, the Lom of the Caucasus, and the Jat of Central Asia. The westwards migration of the Rom in early medieval times is thought to be part of a wider movement of service-providing castes from India – possibly connected with invasions by the central Asian dynasty of the Seljuk Turks, who recruited specialized craftsmen and entertainers as camp-followers. Romani populations who lived in Romanian principalities as slaves until as late as the mid-19th century are also thought to be tied to the Seljuk armies, who may have taken them captive in Anatolia centuries before.

Romani origins in an Indian caste of mobile service-providers would account for the historical prevalence of itinerant trades in Europe among the Roma in late medieval and early modern times. Despite occupying an important service niche, their status as non-settled populations made their situation precarious during periods of political unrest when they were often scapegoated.

Romantic notions

Their travelling lifestyle prompted majority society to adopt an ambivalent view of the Roma. On the one hand they became associated with romantic notions of freedom and spirituality. But at the same time, they became the subject of resentment and suspicion because their behaviour was considered non-conformist and subversive. This social and cultural distance can be detected in the names that the majority gives to the Roma. They are referred to in European languages as ‘Gypsies’ or similar words derived from ‘Egyptian’, an association inspired by their Eastern appearance; or as ‘Tsiganes’ and related words derived in all likelihood from a Seljuk-Turkic designation for ‘pauper’.

Despite their marginalization, the Roma’s role as providers of useful services has also created a certain symbiosis with surrounding populations. This is reflected in Roma communities frequently adopting the dominant religion of their region (while retaining ancient Romani traditions and beliefs), opting in to various local customs and festivities, and acquiring regional languages – which tend to have a strong impact on the structures of respective Romani dialects.

Romani history shows that mobility was not random. Instead, it was contained in particular regions, and connected to established networks of clients, suppliers, and markets. In some European regions Roma were granted explicit settlement rights in the outskirts of towns and villages. In the Ottoman Empire some Romani groups were officially designated as ‘settled’ (in Turkish: ‘Yerli’) and were distinguished from others who were labelled by their trade (such as ‘basket weavers’ or ‘musicians’). Under the Habsburg monarchy in the 18th century, authorities sought to permanently settle and culturally assimilate Romani people.

Roma mobility was usually driven by the need to reach clients, often on a seasonal basis. Reliance on family networks meant that families usually travel together. This gave the impression that Romani people were constantly on the move in large groups or caravans and that they were intrinsically nomadic. Forced evictions, impediments on acquiring property, and violent persecution have reinforced that perception.

Romani migration waves have also come about as a result of political upheavals and persecution, with Roma seeking a permanent change of location in search of more favourable living conditions. In that regard, Roma are no different from other migrants – except for the fact that they tend not to reminisce about a ‘home region’ that they once called their own.

Roma are not the only itinerant traders in Europe. Indigenous populations that specialized in mobile trades have existed for many centuries in most regions and Romani communities have often had contacts with such populations, but tend to remain separate culturally, linguistically, and as kin networks. Yet the designations ‘Gypsies’ and ‘Travellers’ are often applied wholesale and without differentiation.

In recent decades political activists of Romani and other itinerant backgrounds have joined forces to tackle discrimination and exclusion. In the UK, some activists have embraced the abbreviation ‘GRT’ (‘Gypsy, Roma and Travellers’), originally an administrative catch-all term of convenience.

All the while, the Roma’s historical portfolio of mobile trades has been evolving and changing. There is still a notable preference for self-employment, with market stalls, car dealership, carpet restoration, construction and funfairs looming large in the Roma labour market in most European countries. But a growing number of Roma are now finding pathways to a variety of professions. Their spokespersons are also increasingly determined to correct popular misconceptions, and create a true picture and understanding of the Roma, their history and culture.

Yaron Matras is a former Professor of Linguistics at the University of Manchester, and author of I Met Lucky People: The Story Of The Romani Gypsies (Allen Lane, 2014).

This article is from

the January-February 2022 issue

of New Internationalist.

You can access the entire archive of over 500 issues with a digital subscription.

Subscribe today »

Help us produce more like this

Patreon is a platform that enables us to offer more to our readership. With a new podcast, eBooks, tote bags and magazine subscriptions on offer,

as well as early access to video and articles, we’re very excited about our Patreon! If you’re not on board yet then check it out here.

Support us »

Credit: Source link