Business books updates

Sign up to myFT Daily Digest to be the first to know about Business books news.

Among the uses forecast by Thomas Edison for his newly invented phonograph in 1878 was recording the last words of a dying person. As you had to speak loudly into the earliest phonographs in order to be heard, it would have required an unusually hearty form of deathbed speech. But the point stood. Recorded sound made the miraculous possible — to hear the voices of the dead.

This seance-like dimension of Edison’s invention, delivering messages from beyond the grave, is now a major branch of the music industry. Deceased stars are brought back to life through studio trickery, such as the John Lennon vocal demo from 1977 that appeared on The Beatles’ single “Free as a Bird” in 1995. Posthumous releases pile up: Jimi Hendrix released three studio albums in his lifetime but has notched up 13 since his demise. Whitney Houston and Roy Orbison are among the dearly departed to have re-materialised on stage as singing holograms.

Edison, who wanted to design a “spirit phone” in order to communicate with the dead, would have been fascinated. But “the lucrative afterlife of music estates”, as the subtitle of Eamonn Forde’s Leaving the Building puts it, has a dubious side too. Releasing songs without the maker’s consent is ethically questionable, while artistic quality often appears secondary to commercial gain. Rather than exhuming the lost voice of a much-loved performer, posthumous releases can resemble grave robbery.

Leaving the Building is Forde’s follow-up to The Final Days of EMI, his impressive account of the decline and fall of the UK’s last major record label. It is named after the message uttered at the end of Elvis Presley’s concerts to disperse fans: “Elvis has left the building.” The King’s terminal exit in 1977 “was the Big Bang for music estates,” Forde writes — the “business and cultural template that other musical estates all follow”.

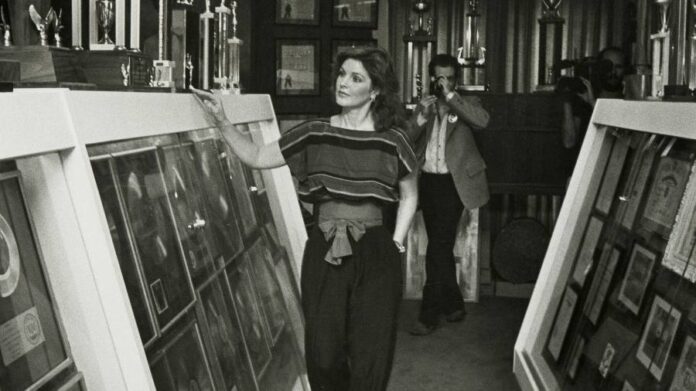

“Elvis didn’t die,” his exploitative manager “Colonel” Tom Parker supposedly remarked. “The body did. It don’t mean a damned thing.” But the real architect of Elvis’s productive posthumous career was his ex-wife, Priscilla Presley. As executor for his sole heir, their daughter Lisa Marie, she rescued the estate from the financially parlous position left by Elvis’s profligacy and Parker’s parasitic self-enrichment. A turning point was the opening of his Memphis mansion Graceland as a museum in 1982. Attracting nearly 700,000 people annually, it gave the singer a shrine. Here was a building that the spirit of the King would never leave.

When Forbes magazine began making “rich lists” of dead celebrities in 2001, Elvis took top spot each year until 2008 (apart from 2006, when Kurt Cobain displaced him). Since 2009, Michael Jackson has dominated this morbid chart. In 2019, Jackson’s estate earned $60m. That was after renewed allegations of child abuse in the documentary Leaving Neverland — an extreme example of the reputational threats that can toxify the memory of a dead star.

Forde touches on numerous case studies, from superstars to cult figures such as Nick Drake, whose music found a larger audience after his death than when he was alive. It is an interesting topic, but its treatment is scattershot. The focus constantly jumps around, like a long series of newspaper articles on the same subject. Despite lots of legal battles, narrative drama is lacking.

“Unfortunately, I’m under an NDA with the estate,” an adviser involved in Prince’s intestate affairs tells Forde. The dead might not speak with one voice, but their administrators share a bloodless language of professional discretion in this informative but piecemeal book.

Leaving the Building: The Lucrative Afterlife of Music Estates by Eamonn Forde Omnibus Press, £20, 496 pages

Ludovic Hunter-Tilney is the FT’s rock critic

Join our online book group on Facebook at FT Books Café

Credit: Source link