When the Fight for $15 campaign took root nearly a decade ago, the notion of raising the minimum hourly wage to a lofty $15 in states and cities across the country seemed like a quixotic quest. After all, the federal minimum wage was — and still is — a meager $7.25 an hour.

No longer, though, is $15 an illusory goal. Starting Saturday, the minimum wage for all workers in the city of San Diego will jump to $15 an hour, a threshold reached — or exceeded — in more than 50 other cities, counties and states. In San Diego County and statewide, the hourly wage floor is rising to $15 for companies with 26 or more employees. For smaller employers, the minimum will increase to $14.

This story is for subscribers

We offer subscribers exclusive access to our best journalism.

Thank you for your support.

It’s a milestone being celebrated by unions, worker advocates and local elected leaders.

But is it?

In a COVID-19 world that has spawned the Great Resignation, desperate employers — from mom and pop businesses to corporate behemoths like Amazon and McDonald’s — are luring workers with promises of pay exceeding local minimum wage mandates, in some cases reaching $18 an hour or more.

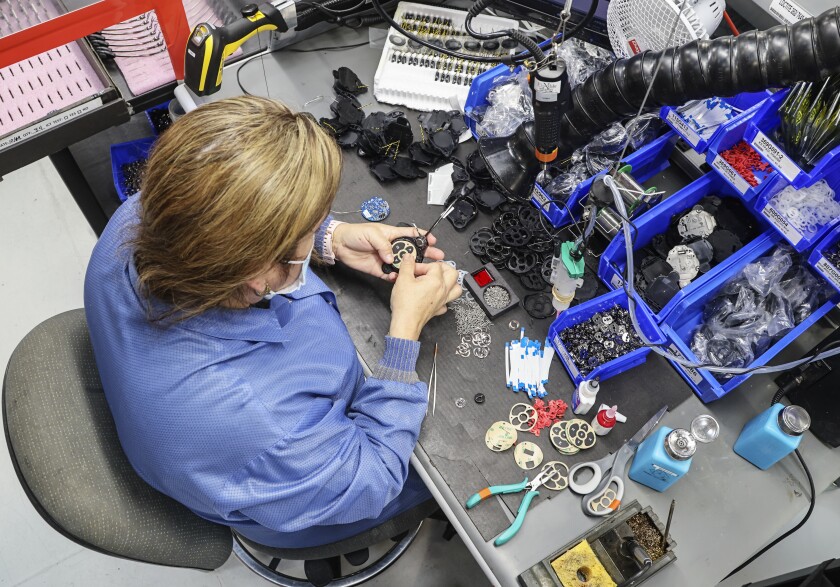

Robert Canseco builds wireless headsets for the Quick Service Restaurant Industry at HM Electronics.

(Eduardo Contreras / The San Diego Union-Tribune)

“Yes, five years ago when we heard $15 an hour, we thought, ‘Oh my God, that’s highway robbery, there will be layoffs. I’ll have to close during certain hours, I can’t afford to pay that,’” recalls Phil Blair, whose staffing company, Manpower San Diego, recruits workers for major employers. “Now, we’re at that $15 and because of current circumstances, no worker wants $15 an hour.

“This new high minimum, which we all thought was very generous, is now useless, because anyone coming into the job market knows they can get more and I’m the first one to tell both employers and employees that.”

To be sure, many of the thousands of jobs lost since the start of the pandemic, when businesses were crushed by a dizzying cycle of government-mandated shutdowns, have since returned. But many still have not. As of November, San Diego County’s total employment in the leisure and hospitality industry, which tends to rely on a higher proportion of lower-wage workers, was still down by 31,000 compared with November 2019 levels.

Nationally, the labor force, as of November, had nearly 2.4 million fewer people than before the pandemic, while Job openings exceeded unemployed workers by 3.6 million as of October, said San Diego economist Lynn Reaser of Point Loma Nazarene University.

Worker shortage means higher wages

San Diego restaurant owner Juan Pablo Sanchez, who has long supported the $15-an-hour wage fight, says he began panicking in August when he wondered if his business would survive the sharp labor shortage he faced as former workers found higher-paying jobs with better hours. More recently, he’s been able to hire additional workers and says he has reconciled himself to the higher wages he must pay to keep them.

“We always had paid a little above minimum wage but now in order to keep our workers, I did increase wages significantly for all our current staff, and for new positions, we also had to significantly increase pay above minimum wage, depending on the position,” said Sanchez, owner of Super Cocina, a fast-casual eatery in Normal Heights.

“This was the first time where the leverage was one-sided, and to some extent, I think it’s good. The downside, with that and inflation, we did have to raise our menu prices a lot more than we’d like. Our payroll has gone from $17,000 every two weeks to $23,000.”

For the first time in a generation, San Diego’s lowest-paid workers have the power to bargain for higher wages given the shrinking labor supply, says employee advocate Alor Calderon, director of the San Diego-based Employee Rights Center.

Brisa Osuna builds wireless headsets for the Quick Service Restaurant Industry at HM Electronics.

(Eduardo Contreras / The San Diego Union-Tribune)

“The imbalance of power before COVID was very stark,” he said. “Employers felt they had the upper hand at every stage but we’re swinging in a different direction. Unskilled workers had more of a stigma attached to them but now they’re being looked at in a different way with this whole discussion of essential workers.”

San Diego-based HM Electronics, which designs, develops and manufactures products for the wireless communication industry, was having such a difficult time finding experienced assemblers that it hired a trainer, said Jack Farnan, vice president of human resources. It is now actively seeking workers with no experience who are willing to learn a new skill, he said.

“So many people have worked so hard for a long time to increase the minimum wage but now with COVID and all of the ramifications that COVID has brought about, that has required companies like ours to search more diligently for those good employees and pay them accordingly. We’ve had to increase employee wages because of this shortage.”

Just two weeks ago, San Diego Mayor Todd Gloria held a news conference attended by local council members and labor union representatives to commemorate the coming minimum wage increase. Gloria, who spearheaded efforts to boost San Diego’s minimum wage when he was on the City Council eight years ago, cheered the new milestone.

“The Fight for 15 is now officially over in the city of San Diego … We have been taking steps toward this milestone since 2016 when city voters approved the Earned Sick Leave and Minimum Wage ordinance,” he said. “A $15 an hour minimum wage will make a huge difference in the lives of working San Diegans.”

Yet just as the Fight for $15 is ending — at least locally — a new statewide campaign to hike the minimum wage to $18 is now beginning. A Los Angeles investor and anti-poverty activist who is spearheading the effort filed papers early this month with the attorney general’s office for a proposed ballot initiative. The Living Wage Act of 2022, as it is called, would gradually increase California’s minimum wage to $18 an hour for all-sized businesses by 2026.

The existing law governing minimum wage for the state as well as the city of San Diego’s ordinance allows for continued increases in the wage floor based on the consumer price index, which gauges inflation.

Speaking at Gloria’s news conference, Kyra Greene, executive director of the San Diego research and advocacy group, Center on Policy Initiatives, underscored the need for still higher pay for San Diego’s lowest-paid workers.

“Fifteen dollars is not enough,” she said. “In the years that it has taken to get to the $15 minimum wage, the cost of living has continued to rise in San Diego. Workers who make $15 an hour still struggle to make ends meet.

Living on $15 an hour

Fast food worker Mauricio Juarez, who shares a three-bedroom home with his wife and his daughter’s family of three, works 56 hours a week at two Jack in the Box restaurants, earning the minimum wage. But the pay, even with the dollar-an-hour raise, is not sufficient to cover rising costs, much less buy a car to replace his 15-year-old Saturn, he said.

“I feel like the store owners and franchise owners make a lot of money and can afford to pay us more and they’re not the ones burning their hands like we are,” said Juarez, 62, who is a cook specializing in making fried food items and will now be earning $15 an hour.

“Right now I have a hernia, it’s very uncomfortable, and if I sought medical attention, they probably would say I need surgery. Then I would have to be out of work for two months and would worry about living expenses like rent. Yes, I have thought about applying for another job, but I know my job, I know the people very well, I know where everything is, and at my age, I just feel like it might be impossible to look for something new.”

Jamie Straza, a longtime McDonald’s franchise operator with four restaurants in San Diego County, acknowledges that in some of her locations she is having to pay new hires more than the minimum wage. She says, though, that pay alone is not what has helped her attract — and retain — employees.

“I can hire at minimum wage. but it’s more the exception, like for a high school student who has limited availability and has never had a job before,” said Straza, who has been an owner and operator for more than 23 years. “Competitive wages are all the talk right now but my turnover is very low, and I think it’s because it’s understanding what is important to your employees, whether it’s flexible hours or tuition assistance.

“But a lot of people are in this bidding war for a starting wage, and it gets them to apply but not necessarily stay.”

Throughout a good part of the campaign for a $15 wage floor, some business groups and economists fretted that such a dramatic pay hike — 67 percent over seven years for San Diego — would lead to unintended consequences. Employment of low-wage workers would fall, they warned, hours would be cut, and automation would make people’s jobs obsolete.

That hasn’t been the case, says labor researcher Ken Jacobs who chairs UC Berkeley’s Center for Labor Research and Education.

“The long story is we’ve gone through 50 years of stagnating or very low wage growth rate at the bottom and in the middle for 40 years and very high wage growth at the top, and in the last year we’ve seen strong wage growth at the bottom but that’s strong growth at an exceptionally low base,” he said. “The preponderance of evidence at this point is that we don’t see reductions in employment as a result of the wage increases. Overall, the most important thing is workers’ earnings have increased, so to the degree there may have been a small reduction in hours, that’s overwhelmed by the large increase in wages.”

The Ocean Park Inn in Pacific Beach does not typically hire its employees at minimum wage except on occasion for temporary seasonal workers, but given the current environment, owner Elvin Lai said he has had to pay even more than normal in hopes of finding people to fill open positions.

“Right now we’re at the $16 mark for starting people,” Lai said in an interview several days before the minimum wage increase to $15. “I don’t know how we’ll even find people at $16. Not all my employees came back for front desk work. Some who had been with me for 10 years decided to do something else. Grocery stores were paying extremely high wages, so I had a few employees who went full time there stocking shelves and working part-time only with me.”

Up until September, Sunny Rapana had been working full-time at the Ocean Park Inn, earning $18 an hour as a front desk supervisor after having been there less than a year. As much as she loved her job, Rapana decided she needed to find a position that allowed for more growth, paid more and had more regular hours. The pandemic and the urgent need of employers to find workers allowed her to make a move. She now works as a claims specialist for Geico insurance company earning nearly $24 an hour, but she continues to work part-time at the hotel.

“I absolutely love working for that hotel and that’s why I still work there part-time but it’s so expensive in California, you can’t always just stay in positions you love, said Rapana, 24, who lives in Pacific Beach with her husband. “You are pressured to move on to something else because of how expensive it is to live here.”

Credit: Source link