When I visited 80 Holland Park on a bright morning in June, the sun cast light over piles of unthumbed coffee-table books and creaseless down duvets draped over vast beds. In a special room designed for hosing down dirty dogs, there was not a single fleck of mud.

Six of the immaculate flats in the new 25-home project — a modern rendering of five classic stucco-fronted, Holland Park town houses — have sold since hitting the market in October last year. But the building is still largely uninhabited.

The latest venture from property developer Christian Candy, 80 Holland Park is a stark departure from Candy’s last grand project.

Along with his brother Nick, Candy built One Hyde Park in 2010, a development that transformed London’s luxury housing market — and continues to test price records for UK flats today.

This time, Christian is going it alone and selling at prices that although high — the asking price on a three-bedroom penthouse is £15.35m — are nowhere near the nine-figure sums paid for flats at One Hyde Park.

“It could not be more different [to One Hyde Park]”, says Roarie Scarisbrick, a prime London buying agent with Property Vision. “It is more BMW than Bentley.”

As the developer synonymous with ostentatious London homes changes tack, could the UK capital’s time as the pre-eminent billionaires’ playground — and the era of its homes as the preferred parking space of global wealth — be coming to an end?

A shifting market

When it was completed in 2010, One Hyde Park in Knightsbridge wasn’t just marginally more expensive than other blocks in the capital, it was in a different league. The first 45 flats sold went for an average of more than £20m each, with one penthouse selling to Ukraine’s wealthiest man for £136m, by far the most expensive flat ever sold in the UK at the time.

The development continues to be a byword for opulence and excess — as well as a lightning rod for anger about London’s unequal housing market. Earlier this year, a flat in One Hyde Park sold for £111m, before stamp duty costs. Another, a penthouse owned by Nick Candy himself, is currently being marketed privately for £175m.

But much has changed since 2010, when the block was a symptom as well as a cause of a runaway market. Scrambling for safe places to park cash, and encouraged by rock-bottom interest rates and successive rounds of quantitative easing, the international ultra-wealthy poured money into property in “global cities” such as London and New York.

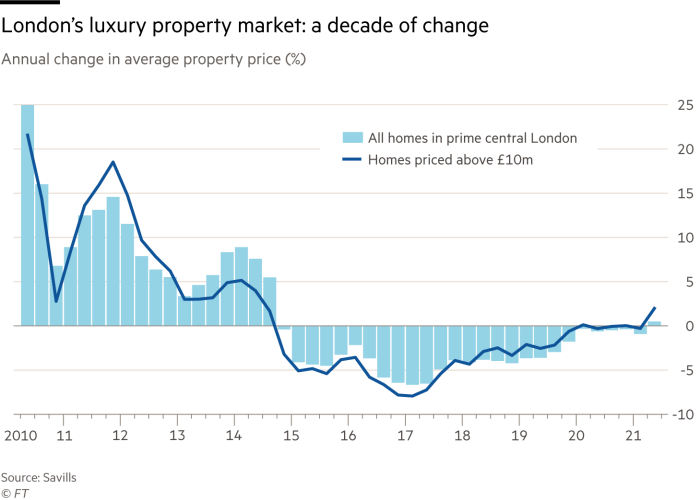

Any damage the financial crash did to high-end house prices in London was rapidly reversed. Between 2010 and 2013, London had the fastest-growing prime property market in the world, according to estate agent Knight Frank. By the third quarter of 2013, its luxury homes were the most expensive in the world — at $3,995 per sq ft, compared with $3,917 in Hong Kong and $3,101 in Manhattan.

The torrent of cash entering the city’s property market was still so great in 2014 that Boris Johnson, at the time London mayor, announced: “London is to billionaires what the jungles of Sumatra are to the orang-utan. It is their natural habitat.”

But in the years since, the jungle has become harder to navigate.

“Planning has got tougher, taxes have got higher. The landscape has changed enormously,” says Rupert des Forges, a partner at Knight Frank who has spent decades brokering deals in London’s so-called super-prime market, where the entry fee is £10m — and who shows me around 80 Holland Park.

Targeted interventions by then-chancellor George Osborne increased the stamp duty burden for buyers in 2014 and again in 2016. At the same time, the market had to absorb reforms to taxation for homes owned through offshore and domestic companies, changes to inheritance tax and capital gains tax for non-UK residents — to say nothing of the tighter money-laundering regulations brought in over the past few years.

With Johnson’s successor as mayor Sadiq Khan introducing higher targets for affordable housing delivery, development economics have looked less favourable and prompted many private builders to look beyond London.

Add Brexit and the pandemic’s travel restrictions into the mix, and the capital has not shared in the runaway house price growth seen across much of the country over the past 13 months.

On Tuesday, building society Nationwide put the annual growth of the average UK house price in June at 13.4 per cent, the fastest growth since November 2004.

But London has lagged, particularly in the market for the most expensive homes. Prices for £1m homes in central areas have fallen by about 17 per cent since 2014, according to LonRes, which monitors the London market.

The optics of super-prime development have changed too. The mayor who celebrated London’s position as the habitat of billionaires is now the prime minister pursuing a “levelling-up” agenda explicitly aimed at reducing inequality between London and the rest of the UK.

In the midst of a health crisis, and an attendant recession, flashy interiors and price tags in the tens of millions are more likely to alienate than inspire.

Ballymore, a high-end but not super-prime developer with a number of projects in London, recently cut the ribbon on a swimming pool suspended 10 floors up between two blocks of luxury apartments.

The 25-metre long pool is intended as the pièce de résistance of Ballymore’s Battersea development, but the show of opulence has been lambasted by critics — including in the pages of the Financial Times — who claim it is inappropriate in a city suffering an acute housing shortage.

Who are the Candy brothers?

Nicholas Candy

Age: 48

Nicholas and his brother Christian started on the property ladder in 1995, renovating a one-bedroom flat in Earl’s Court with a £6,000 loan from their grandmother, writes Kristina Foster.

After four years of developing flats in his spare time, Nicholas was able to give up his job in advertising to found Candy & Candy (later renamed Candy London) alongside his brother.

In 2004, the pair embarked on their most ambitious project to date, One Hyde Park in Knightsbridge, which broke records for the most expensive residential development in the world.

Christian Candy

Age: 46

Christian was working as an investment banker when he quit to go into property full-time with Candy & Candy.

In 2004, he established the CPC Group in Guernsey. Although focusing on exclusive international residential developments, such as the Richard Meier-designed 9900 Wilshire in Beverly Hills, CPC Group is also known for its high-profile projects in London. In 2007, it bought Chelsea Barracks in a joint venture with the Qatari government for £959m, believed to be the most expensive residential property deal in the UK.

Christian resigned as a director of Candy & Candy in 2011.

Has Candy read the room?

Candy’s new development is subtler, and the pricing is more sober than his previous outing at One Hyde Park. Two-bedroom flats start at £2.6m in 80 Holland Park. A three-bedroom flat has just sold for £9.1m, or £4,335 per sq ft. That’s a record for the W11 postcode, according to the developer, but still short of super-prime territory.

“Christian Candy knows the market better than anyone. He’s catering to

a very different audience in Holland Park to that in Knightsbridge,”

says Scarisbrick.

More than most high-end developments, 80 Holland Park is pitched at domestic rather than international buyers. Prospective buyers are still “migrants”, says des Forges, but only from as far afield as “Knightsbridge or Chelsea”. That is an advantage at a time when travel restrictions are hampering the overseas shopping trips of the hyper-wealthy.

The developers decided against marketing flats for sale before the entire building was complete, an unusual move when many developments rely on deposits paid against unbuilt apartments in order to finance construction.

According to des Forges, Candy was deep-pocketed enough to go without cash from “off-plan” deals. But he also acknowledges that a sluggish market for luxury apartments in London had an impact.

“Off-plan sales have slowed with the market slowdown . . . it’s easy to sell something ahead of completion in a buoyant market.”

The development is likely to be Candy’s “last hurrah,” according to des Forges. “Residential development is a mercurial business, people come and go,” he adds.

Tim Craine, head of research at Molior London, which monitors the property market, is more blunt: “Most developers do one cycle and quit. Either you make a load of money or go bust; either way you quit.”

The impact of Covid-19

In the 12 months to the end of March 2020, the month when pandemic-related restrictions were first put in place in the UK, Knight Frank recorded some 112 super-prime sales with a combined value of £2.35bn. In the next 12 months, which took in three national lockdowns, there were just over 80 sales, totalling £1.35bn.

“We’ve had a real issue on deals at £20m-plus: that’s the big money coming over from elsewhere in the world . . . People don’t want to isolate for five to 10 days,” says Charles McDowell, a buying agent.

But the reality is that the kind of people with at least £10m available to buy a home will not be constrained for long, even by a pandemic. Nor are they likely to have suffered from the economic chaos which has accompanied it. The total wealth of billionaires worldwide rose by $5tn to $13tn in 12 months during the pandemic, according to Forbes, as government stimulus flooded financial markets.

Happily for anyone selling superyachts or mega mansions, the super-rich are proliferating.

“The thing you have to remember is that there are huge numbers of people with huge amounts of wealth. I get calls about people I’ve never heard of who have untold wealth,” says McDowell. “Will billionaires come to London? They will.”

Deals in the super-prime sector can be notoriously secretive. Estate agents often won’t be, or can’t be, drawn on details. “I have so many NDAs [non-

disclosure agreements] they are like confetti,” says one. But it is possible to catch glimpses, which give a sense of a market in which tastes are changing — and despite Christian Candy aiming his new development at a more domestic, lower-value market, not all buying agents agree that that is where the demand is right now.

“Normally I would have one [client looking for a home] at £3m, one at £5m, one at £7m. At the moment it’s only at the very high end,” says Nathalie Hirst, a London-focused buying agent. She is currently searching on behalf of clients with price ranges of £10m, £17m and £50-£150m. “It’s the best client list in terms of spending power I’ve ever had . . . I think super-prime is very much alive and well,” she says.

Travel restrictions can still get in the way of deals. “I’m spending a lot of time taking videos for clients,” says Hirst. Typically, buyers are “75 per cent from overseas, mostly the Middle East or Hong Kong. It’s still that,” says Paul Roshan, a broker who is currently marketing office buildings in Belgravia and on Regent’s Park to residential developers to convert into super-prime homes.

Waiting for the right billionaire to come along

The billionaires may still be coming, but their tastes have changed, says Rory Penn who, as head of Knight Frank private office, advises the wealthy on their property purchases. A decade ago, the glitz of One Hyde Park set the tone and proved adept at attracting buyers from the Middle East and Russia, at the time the dominant property shoppers from overseas.

Now, he adds, “There’s such a variety of buyers in London: from Europe, the US, Asia as well as the other markets. The style today is less ostentatious, slightly more subtle, a more homely look . . . antique bronze as the metal of choice, not shiny brass or gold.”

While trade in the prime market has become more laboured in recent years, at the very top end prices have continued to increase as tastes have become more refined. The most prestigious flats can trade for close to £10,000 a square foot, according to agents, though there are only a handful of newly built developments likely to come close to that bracket: such as Lodha’s No 1 Grosvenor Square development, the Peninsula on Hyde Park Corner and Chelsea Barracks.

Another which might is the Glebe, an eight-home development in Chelsea that has been compared to One Hyde Park. There are parallels in the pricing — the penthouse of the Glebe is being marketed for close to £100m — but beyond that “there is no comparison”, says David Salkin, a director at Orion Capital, the building’s developer.

Where the Candys’ block is all noise — glass-fronted and jutting out into Knightsbridge — the Glebe is “180 degrees different: small, discreet, very confidential. Seven of the apartments have access from a private garage. Its aim is not to be seen,” says Salkin.

At present, the Glebe might be fulfilling that role too well. One unit has sold since the project was completed at the turn of this year. “That discreet market is much harder . . . They take a long time to sell, you have to wait for that billionaire to come along,” says McDowell, the buying agent.

Typically well-funded, developers of London’s most expensive properties can wait it out. “While prices have become seemingly ludicrous, they do get through them,” says Scarisbrick. Already-built prime properties have declined in value over the past six years, but “that hasn’t been reflected in that new-build world. [The developers] put their fingers in their ears and kept shouting and got away with it,” he says.

“It’s just a question of waiting, we haven’t compromised anything. We stand steady,” says Salkin. “Every pot will find its lid.”

George Hammond is the FT’s property correspondent

Follow @FTProperty on Twitter or @ft_houseandhome on Instagram to find out about our latest stories first

Credit: Source link