Carney took the long way to Nightbirds. This first hot spell of the year was a rehearsal for the summer to come. Everyone a bit rusty, but it was coming back—they took their places. On the corner, two white cops re-capped the fire hydrant, cursing. Kids had been running in and out of the spray for days. Threadbare blankets lined fire escapes. The stoops bustled with men in undershirts drinking beer and jiving over the noise from transistor radios, the d.j.s piping up between songs like friends with bad advice. Anything to delay the return to sweltering rooms, the busted sinks and clotted flypaper, the accumulated reminders of your place in the order. Unseen on the rooftops, the denizens of tar beaches pointed to the lights of bridges and planes.

The atmosphere in Nightbirds was ever five minutes after a big argument with no one telling you what it had been about or who’d won. Everyone in their neutral corners replaying K.O.s and low blows and devising too late parries, glancing around and kneading grudges in their fists. In its heyday, the joint had been a warehouse of mealy human commerce—some species of hustler at that table, his boss at the next, marks minnowing between. Closing time meant secrets kept. Whenever Carney looked over his shoulder, he frowned at the grubby pageant. Rheingold beer on tap, Rheingold neon on the walls—the brewery had been trying to reach the Negro market. The cracks in the red vinyl upholstery of the old banquettes were stiff and sharp enough to cut skin.

Less dodgy with the change in management, Carney had to allow. In the old days, broken men had hunched over the phone, hangdog, waiting for the ring that would change their luck. But, last year, the new owner, Bert, had had the number on the pay phone changed, undermining a host of shady deals and alibis. He also put in a new overhead fan and kicked out the hookers. The pimps were O.K.—they were good tippers. He removed the dartboard, this last renovation an inscrutable one until Bert explained that his uncle “had his eye put out in the Army.” He hung a picture of Martin Luther King, Jr., in its place, a grimy halo describing the outline of the former occupant.

Some regulars had beat it for the bar up the street, but Bert and Freddie had hit it off quickly, Freddie by nature adept at sizing up the conditions on the field and making adjustments. When Carney walked in, his cousin and Bert were talking about the day’s races and how they’d gone.

“Ray-Ray,” Freddie said, hugging him.

“How you doing, Freddie?”

Bert nodded at them and went deaf and dumb, pretending to check that there was enough rye out front.

Freddie looked healthy, Carney was relieved to see. He wore an orange camp shirt with blue stripes and the black slacks from his short-lived waiter gig a few years back. He’d always been lean, and when he didn’t take care of himself quickly got a bad kind of thin. “Look at my two skinny boys,” Aunt Millie used to say when they came in from playing in the street.

They were mistaken for brothers by most of the world, but distinguished by many features of personality. Like common sense. Carney had it. Freddie’s tended to fall out of a hole in his pocket—he never carried it long. Common sense, for example, told you not to take a numbers job with Peewee Gibson. It also told you that, if you took such a job, it was in your interest not to fuck it up. But Freddie had done both of these things and somehow retained his fingers. Luck stepped in for what he lacked otherwise.

Freddie was vague about where he’d been lately. “A little work, a little shacking up.” Work for him was something crooked; shacking up was a woman with a decent job and a trusting nature, who was not too much of a detective. He asked after business in Carney’s furniture store.

“It’ll pick up.”

Sipping his beer, Freddie started in on his enthusiasm for the new soul-food place down the block. Carney waited for him to get around to what was really on his mind. It took Dave “Baby” Cortez on the jukebox, with that damn organ song, loud and manic. Freddie leaned over. “You heard me talk about this nigger every once in a while—Miami Joe?”

“What’s he, run numbers?”

“No, he’s that dude wears that purple suit. With the hat.”

Carney thought he remembered him maybe. It wasn’t like purple suits were a rarity in the neighborhood.

Miami Joe wasn’t into numbers. He did stickups, Freddie said. Knocked over a truck full of Hoovers in Queens last Christmas. “They say he did that Fisher job, back when.”

“What’s that?”

“He broke into a safe at Gimbels,” Freddie said. Like Carney was supposed to know. Like he subscribed to the Criminal Gazette or something. Freddie was disappointed but continued to puff up Miami Joe. He had a big job in mind, and he’d approached Freddie about it. Carney frowned. Armed robbery was nuts. In the old days, his cousin had stayed away from stuff that heavy.

“It’s going to be cash, and a lot of jewelry that’s got to get taken care of. They asked me if I knew anyone for that, and I said I have just the guy.”

“Who?”

Freddie raised his eyebrows.

Carney looked over at Bert. Hang him in a museum—the barman was a potbellied portrait of hear no evil. “You told them my name?”

“Once I said I knew someone, I had to.”

“Told them my name. You know I don’t deal with that. I sell home goods.”

“Brought that TV by last month—I didn’t hear no complaints.”

“It was gently used. No reason to complain.”

“And those other things, not just TVs. You never asked where they came from.”

“It’s none of my business.”

“You never asked all those times—and it’s been a lot of times, man—because you know where they come from. Don’t act all ‘Gee, officer, that’s news to me.’ ”

Put it like that, an outside observer might get the idea that Carney trafficked quite frequently in stolen goods, but that wasn’t how he saw it. There was a natural flow of goods in and out and through people’s lives, from here to there, a churn of property, and Ray Carney facilitated that churn. As a middleman. Legit. Anyone who looked at his books would come to the same conclusion. The state of his books was a prideful matter with Carney, rarely shared with anyone because no one seemed very interested when he talked about his time in business school and the classes he’d excelled in. Like accounting. He told this to his cousin.

“Middleman. Like a fence.”

“I sell furniture.”

“Nigger, please.”

It was true that his cousin did bring a necklace by from time to time. Or a watch or two, topnotch. Or a few rings in a silver box engraved with initials. And it was true that Carney had an associate on Canal Street who helped these items on to the next leg of their journey. From time to time. Now that he added up all those occasions, they numbered more than he’d thought, but that was not the point. “Nothing like what you’re talking about now.”

“You don’t know what you can do, Ray-Ray. You never have. That’s why you have me.”

“This ain’t stealing candy from Mr. Nevins, Freddie.”

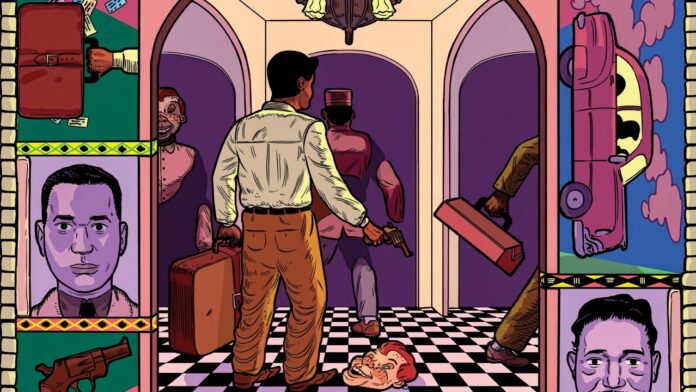

“It’s not candy,” Freddie said. He smiled. “It’s the Hotel Theresa.”

Two guys tumbled through the front door, brawling. Bert reached for Jack Lightning, the baseball bat he kept by the register.

Summer had come to Harlem.

At Nightbirds, Freddie had made Carney promise to think about it, knowing that he usually came around if he thought too long about one of his cousin’s plots. A night of Carney staring at the ceiling would close the deal, the cracks up there like a sketch of the cracks in his self-control. It was part of their Laurel-and-Hardy routine: Freddie sweet-talks Carney into an ill-advised scheme, and the mismatched duo tries to outrun the consequences. Here’s another fine mess you’ve got me into. His cousin was a hypnotist, and suddenly Carney’s on lookout while Freddie shoplifts comics at the five-and-dime, or they’re cutting class to catch a cowboy double feature at Loew’s. Two drinks at Nightbirds, and then dawn’s squeaking through the window of Miss Mary’s after-hours joint, moonshine rolling in their heads like an iron ball. There’s a necklace I got to get off my hands—can you help me out?

Whenever Aunt Millie interrogated Freddie over some story the neighbors told her, Carney stepped up with an alibi. No one would ever suspect Carney of telling a lie, of not being on the up and up. He liked it that way. For Freddie to give his name to Miami Joe and whatever crew he’d thrown in with—it was unforgivable. Carney’s Furniture was in the damn phone book, in the Amsterdam News, when he could afford to place an ad, and anyone could track him down.

Carney agreed to sleep on it. The next morning, he remained unswayed by the ceiling. He was a legitimate businessman, for Chrissake, with a wife and a kid and another kid on the way. He had to figure out what to do about his cousin. It didn’t make sense, a hood like Miami Joe bringing small-time Freddie in on the job. And Freddie saying yes, that was bad news.

This wasn’t stealing candy, and it wasn’t like when they were kids, standing on a cliff a hundred feet above the Hudson River, tip of the island, Freddie daring him to jump into the black water. Did Carney leap? He leaped, hollering all the way down. Now Freddie wanted him to jump into a slab of concrete.

When Freddie called the office that afternoon, Carney told him it was no-go and cussed him out for his poor judgment.

The robbery was in all the news.

Customers carried rumors and theories into the furniture store. They busted in with machine guns and I heard they shot five people and The Italian Mafia did it to put us in our place. This last tidbit put forth by the Black nationalists on Lenox Ave., hectoring from their soapboxes.

No one was killed, according to the papers. Scared shitless, sure.

Credit: Source link